Spoonie Culture and the Backlash of Misunderstanding from Other Generations

Spoonie Culture and the Backlash of Misunderstanding from Other Generations

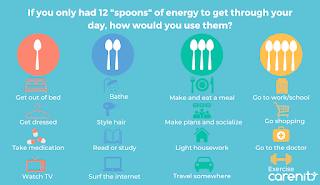

Picture credit: Carenity.com

Chronic Illness is difficult to explain without sounding like a medical dictionary at the best of times.

Especially when it comes to simply not knowing how to describe energy levels or the lack of focus, especially if you don’t have a diagnosis.

Many like me have started to adopt the Spoon Theory to explain how much focus, energy, emotional strength and motivation we have.

It was originally thought up by another who has a chronic disease, Christine Miserandino, who lives with Lupus - a disability where the defensive antibodies attack the body’s useful cells, thinking them a threat to the immune system.

This limits what they can accomplish on bad days compared to good ones, but it varies from person to person.

Struggling to explain this to her friend, Miserandino eventually gazed around the café they were at and started to explain using spoons from the available cutlery to illustrate the energy she had to use for all the tasks that day and how some tasks took more than others.

When she took away a spoon or two for each of the activities she had to do that day, which left her with more things she had to do than spoons to illustrate them, this made the friend she’d gone to the Café with cry at the realisation that this what she experienced daily.

This gained incredible popularity when Miserandino wrote up a small essay on her blog, But You Don’t Look Sick. It gained popularity with the chronic illness community and became a great explainer for the next theory that explained it in similar ways… The Unified Cutlery Theory or Kitchen Drawer Theory.

The Kitchen Drawer Theory is thinking of the other cutlery types similar to spoons.

When you run out of spoons, you use forks to get rid of something stressful.

A task that will get something done the fastest that is causing you to panic, like if the postman is at the door and you spent fifteen minutes stressing over what your disability will find easy to wear. Finally, you throw on yesterday’s hoodie and a pair of tracksuit trousers because it’s easier than figuring out if your disability and motivation will work together to do up a series of buttons.

The next in the theory is knives. These represent something you must push yourself to your limits to do because you have no spoons.

This may even cause you emotional, physical and mental exhaustion, and you cannot do anything else for days.

Even the lack of understanding from others can be a knife.

Recently, The Daily Mail’s Article accusing people of spreading a kind of anxiety and ‘fake illnesses’ under the #Spoonie Hashtag online has been harmful to the community.

Usually, the hashtag is used to spread awareness of the physical, mental and emotional effects of chronic illness and immunodeficiency conditions; sometimes, this is used by people who turn out to be using the hashtag for online attention, but rarely.

The Daily Mail article has even distressed many of the community. There is more controversy around its removal and the harmful messages it spreads - not even crediting the screenshots it contains from people’s social media.

There is a petition asking for its removal, with implications of quotes directly from the article, such as the prominent tagline, reading “Addicted to being sad. Teenage girls with invisible illnesses known as spoonies post TikToks of themselves crying of in hospital to generate thousands of likes,” and, “Thousands of teens are banding together on social media as part of the movement, which also encourages them to lie to doctors in order to get the diagnosis that they want.”

Headlines under videos taken without permission with no safety for those who posted them from any negativity; one description even reads, “Others join groups to discuss the negative side effects to their conditions, and often end up competing with each other for who is ‘sickest’”.

This kind of negativity towards communities with illnesses needs compassion and understanding, not witch hunts of people trying to prove that someone is ‘faking it’ just by looking at them and having no medical training or the right to demand someone share a medical diagnosis if they have one.

It is complex enough sometimes for chronically ill people to find a doctor that will conduct tests to rule out what they don’t have, especially if the medical condition is rare or unknown.

They even falsified an interview with Morgan Cooper, a person with a chronic illness, who confirmed to Petition owner Nia that she was never asked for an interview and had no idea that her identity was being used for the article.

The fact that this is spreading more negativity towards groups meant to help people, especially those that have guilt over the things they can and can’t do that everyone has the energy to do, from a load of washing that has to be put in the dryer, to not having any spoons to attend a friend’s party, is damaging to the mental health of already vulnerable people.

It doesn’t stop with younger people, either. Older people who are living with disabilities in perhaps their late twenties and thirties still experience a lack of compassion and understanding from others.

Rachel Blank, a full-time senior product designer, was diagnosed with severe Crohn’s Colitis, an autoimmune disease that primarily affects the gastrointestinal tract.

Since she was eleven, she knew she would have to work harder at school, around the house and even in social relationships, especially with being a Spoonie and not having almost finite energy like other people do.

Even when it came to working professionally, her disability was seen as something that inconvenienced others, even though she tried to minimise and hide her condition from her colleagues.

According to the article she wrote for Inclusion Hub, she was afraid to admit that she had the condition for fear that she may be considered lazy and unproductive. This stigma hits many people who live with disabilities and work.

The only people Rachel told were the Human Resources department and her line Manager, for fear of stigma, which meant that she was overcompensating to work as hard as everyone else.

For Spoonies, doing this makes us sicker, and while it is understandable to want to be as productive as the standard set by other co-workers, or perhaps the team you work in, it can be detrimental to our health in the long run.

This is where Rachel experienced the stigma she feared the most. She ‘Didn’t look sick enough.’ for her Colleagues or boss and was reprimanded for using “reasonable accommodations” at work when she did need them.

She was even told she was ‘taking advantage or exaggerating’ about her use of the Work from Home scheme, and “-was once told by my manager that I looked fine in all my pictures on social media, where I appeared to be enjoying life, smiling, and socialising. Translation: “How could I POSSIBLY be so sick if I look so happy and active in my Facebook pictures?”

“Another time, I was told that despite giving months of notice, I was inconveniencing my boss by having my colon removed. I was expected to be working within two days of my surgery.”

While Rachel may be American, this is something people have experienced in England, also.

When I did an article about Autism diagnosis being discovered in later life, many of my close friends who had been diagnosed and those still waiting struggled with empathy and understanding in the workplace.

When I asked people who suspect that they are on the Autistic spectrum if there were any barriers they faced through lack of understanding from employers or similar, with no official diagnosis, I found that their employers or family struggled to understand and accommodate them unless there was a diagnosis.

“Yeah, because I’ve had feedback from people that have been like, “Oh, it took me a long time because I yet don’t have a diagnosis. Even though I have these other conditions that it would help to have, I don’t know, a raised chair or a special keyboard. If my employer doesn’t see a diagnosis….”

“They obviously don’t want to spend what little budgets they have or something on this that might help me, you know, there there’s no…” (guidelines for someone without a diagnosis needing equipment at work, currently.)

That was just one feedback from many friends and people I had contacted at the time. A diagnosis seems to make people accept or appear sceptical, and some people with disabilities, like Rachel, don’t want to share medical information because of that attitude and stigma.

Even Doctors can be sceptical when diagnosing people or when discussing possible surgeries, which is something Laura Kiesel, writing for Medium, has experienced.

She was having a phone call with a Doctor well known for a surgery she wanted that would hopefully help with a pain she’d had in one leg from nerve problems after having severe herniation and cysts in her spine.

Instead, the Doctor told her it wasn’t safe due to her having complexities, with multiple conditions that affected her body, even being interested in her condition and life with them.

For me, this is another point which receives both stigma and an incredible amount of ignorance. Being fascinated with someone’s body and how it functions or doesn’t with multiple disabilities can often make the feel like they are just a bunch of diagnoses.

It made me feel like I was a science experiment, some kind of lab rat under a microscope, more than a person.

For Laura, it felt weird, but not something she was unused to hearing.

“As we talked, it became clear that this Doctor, like many before, was cynical about my diagnoses. Did I really have all the degenerative damage in my spine and hips I claimed even though I was only in my thirties? He asked me if the picture on my website was current. “It’s from just last year,” I answered. He asked me if I had gained a lot of weight or lost some of my hair in the year since the photo was taken. I hadn’t. He asked me more than once if I was being honest. I was becoming increasingly frustrated, and then he finally said, “It’s clear you have a lot of things going haywire in your body, but I have to admit, you are going to have a hard time getting doctors to believe you because of how you present physically.”

“It’s a sentiment I’ve grown used to receiving, though it’s usually not presented in such blunt terms by a member of the medical community willfully admitting the biases of the profession. Despite numerous blood tests, biopsies, and lab images I have to prove my case, I run into this reaction on a routine basis.”

Even her interview with Harvard about Chronic illness shares many of the same issues that I and many others I know who are Spoonies face almost every day.

How this affects people mentally can vary, as, like our physical pain, we often mask our emotional and mental stress as just a side effect of disability.

According to World Psychiatry, mental health and physical disability are often together and tend to cause emotional problems while worsening someone’s disability. This is even before considering the effect of someone’s scepticism, whether they are your boss, family member or a stranger.

You can even have stigma internally, feeling as if you must be ‘faking or making up your pain and symptoms when they are unknown, as part of a rare condition or difficult to diagnose.

When it comes to other people’s stigma, there is another issue for people like me.

It’s important to educate people in order to fight stigma and change the attitudes of Doctors and the regular person who asks, but it’s not someone’s job to have to educate people on how they should treat someone with a Disability, whether mental, physical, emotional or all three.

It’s infuriating for many to receive such attitudes every day, just wanting to get through as much of their daily routine as they can.

We don’t need more stigma, and it’s not our job to share diagnoses or fight for you to believe us. We just need kindness and empathy without being sympathised with as if we are children.

Respect and Understanding are key.

Comments

Post a Comment